Did you enjoy this episode? Help support the next one!

Resources

- The Life of Francis Marion, by W. Gilmore Simms

- The Patriot (2000) – IMDb

- The Patriot (2000 film) – Wikipedia

- The Patriot (2000) – Synopsis

- The Patriot: Film Fact or Fiction

- Francis Marion – Wikipedia

- The Swamp Fox | History | Smithsonian

- American Heroes: Francis Marion, South Carolina’s “Swamp Fox” – A Patriot’s History of the United States

- Francis Marion University – News: 2000: Life of Gen. Francis Marion inspiration for “The Patriot”

- Francis Marion

- Francis Marion Foils the British | HistoryNet

- Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion (1732 – 1795) – Find A Grave Memorial

- The Patriot and the Real Francis Marion

- Francis Marion, Swamp Fox – My SC History

- Light Horse Harry Lee | Stratford Hall

- Continental Army

- Chapter 3: The American Revolution: The First Phase

- The Revolutionary Years

- William Gilmore Simms, 1806-1870

- Francis Marion: the Swamp Fox book by Hugh F. Rankin | 1 available editions | Alibris Books

- The French and Indian War in the American South

- Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton – Cowpens National Battlefield (U.S. National Park Service)

- Charles Cornwallis – American Revolution – HISTORY.com

- Banastre Tarleton – Wikipedia

- Battle of Eutaw Springs – American Revolution

- The American Revolution – (The Battle of Eutaw Springs )

- The Battle of Cowpens – Cowpens National Battlefield (U.S. National Park Service)

- Battle of Cowpens – Wikipedia

- Battle of Cowpens – American Revolution – HISTORY.com

Disclaimer: Dan LeFebvre and/or Based on a True Story may earn commissions from qualifying purchases through our links on this page.

Transcript

Note: This transcript is automatically generated. There will be mistakes, so please don’t use them for quotes. It is provided for reference use to find things better in the audio.

Our movie today opens with a hatchet placed into a chest. Mel Gibson’s voiceover mentions something vague about his sins coming back to haunt him.

After this, it’s a sunny day with children giggling as the mail gets delivered to a large plantation surrounded by lush, green fields. Finally, we’re introduced to Mel Gibson’s character, Benjamin Martin, as his children rush into the barn to tell him of the post rider. We see a bit of text on screen that says it’s South Carolina in the year 1776.

This opening sequence comes to a close when Benjamin and his son, Gabriel, open the mail to find out the Continental Congress plans to make a declaration of independence by July.

Gabriel Martin, by the way, is played by Heath Ledger.

He also wasn’t real. Gabriel Martin wasn’t a real person because his father, Mel Gibson’s character Benjamin Martin, also wasn’t real.

The character of Benjamin Martin was based on a man named Francis Marion, and Francis didn’t have any children at all. In fact, the filmmakers wrote the part of Benjamin Martin specifically for Mel Gibson and instead wrote in the number of children to be the same number of children Mel had.

That’s why Benjamin Martin had seven children in the movie. And since I’m assuming you’ve seen The Patriot, you probably know how much the movie relies on those children throughout the storyline, so you probably also are getting an idea of how accurate the film is going to be.

Although it’s worth pointing out that the real Francis Martin was the son of Gabriel Martin. He also had an older brother named Gabriel, no doubt named after his father. So maybe that’s where the filmmakers got Heath Ledger’s character’s name.

Oh, and by the way, the mention of the Continental Congress is actually correct here. Even though the United States didn’t declare independence until July 4th, 1776, the First Continental Congress convened in 1774, so it’s very possible that Benjamin Martin would’ve been reading about them in the post before July of 1776.

Of course, if Benjamin Martin were real, that’d be possible.

Even though the Continental Congress existed at that point, there’s some interesting points to make about the timeline here. We already learned that the First Continental Congress met in 1774. From September 5th to October 26th, 1774, to be specific.

They met again on May 10th, 1775, and it was during this first meeting in May of 1775 that the Second Continental Congress passed a resolution for independence at the Philadelphia State House. The resolution was to be carried out on July 2nd, 1776.

According to the letter that Heath Ledger’s character reads to his father in the movie, the New York and Pennsylvania assemblies are debating independence. Then Heath’s version of Gabriel Martin goes on to say the Continental Congress will make a declaration of independence by July.

It’s hard to say if the movie is accurate or inaccurate here because the movie is very vague. By that, I mean all we know is that it’s sometime in the spring of 1776—I’m assuming spring since Mel Gibson’s character asks his sons about planting the fields—and he receives word of independence by post.

There’s not a mention of the fact that the resolution for independence had already been passed, but that doesn’t mean it’s inaccurate. After all, even though it was the news of the time, it’s not like every letter carried such news.

As Mel Gibson’s version of Benjamin Martin ponders this news, Heath Ledger’s Gabriel reads of new recruits joining the Continental Army.

As best as I can tell, the article itself is fictional because there’s no documentation of a listing of names like Ezra Straw, John Warren, James Potter, Thomas Mills or Benjamin Ward in papers of the time. That doesn’t mean those aren’t real people—for example, we know there was a Benjamin Ward at the time—but that also doesn’t mean the filmmakers based those names off anything other than random names commonly used at the time.

The plot point for the film, though, is one that was very true. As it became more obvious that the Continental Congress was going to declare independence, that’d mean war was all but guaranteed. As such, one of the first things the fledgling American government would need to do was to set up an army that could help ensure they could stay the American government.

Back in the movie, Benjamin Martin and his children travel to Charles Town where he’s to attend an assembly, while his children stay with their aunt, Charlotte Selton. Charlotte is played by Joely Richardson.

In the movie, there’s a brief moment when we see Benjamin and Charlotte on screen for the first time where Benjamin mentions his children are from good stock on their mother’s side.

The implication here being that Benjamin is a widower and his children’s mother, Susan, was Charlotte’s sister.

All of that is made up.

Like the Martin family, Charlotte Selton is a fictional character. Not only that, but her appearance is one that strays quite a bit from the real story.

You see, the real Francis Marion, the man on which Mel Gibson’s character was based, didn’t marry until later in his life, at the age of 54. His wife was a woman named Mary Esther Videau, and the two married on April 20th, 1786, well after the events in the movie.

Not only that, but Francis and Mary didn’t have any children together. So it’d seem there’s quite a bit of creative freedom for The Patriot’s storyline.

Oh, and as a side note, the movie is accurate in its spelling of Charles Town. They spell it as two words, Charles and Town. Today it’s Charleston, one word, but back then it was indeed two words. The changes from Charles Town to Charleston didn’t happen until after the Revolutionary War in 1783.

Back in the movie, while in Charles Town, South Carolina, we meet Colonel Harry Burwell for the first time. He’s played by Chris Cooper.

The character of Colonel Harry Burwell is another fictional character, but like Benjamin Martin he was based on a real person. Chris Cooper’s character was based on a man named Henry Lee III.

To get a bit of background on Henry Lee, after graduating from Princeton in 1773, he returned home to Virginia where he was commissioned as a Captain in the fifth group of Virginia Light Dragoons. His adept horsemanship and skill in battle earned him a promotion to Major as he led a group of mixed cavalry and infantry many referred to as Lee’s Legion.

In one instance, he surprised British soldiers at Paulus Hook, New Jersey. Thanks to his leadership, only one man was lost while they managed to capture over 400 British soldiers. This and other similar events helped earn him a promotion to Colonel as well as the nickname “Light-Horse Harry”.

However, that instance in New Jersey took place in 1779. So Colonel “Light-Horse Harry” Lee wasn’t actually a Colonel during the events in the movie, so if the movie were accurate here trying to pass off Harry Burwell as Henry Lee, it wouldn’t be Colonel Burwell but instead Major Harry Burwell.

Anyway, the story line here in the movie is that Colonel Burwell is there to help convince the assembly to vote a levy. Speaking in front of the assembly, Colonel Burwell says they expect a declaration of independence to come from Philadelphia and asks that South Carolina become the ninth colony to levy taxes to help raise money for an army.

While in the assembly, Mel Gibson’s Benjamin Martin explains that while he’s all for the colonies governing themselves, he doesn’t want to go to war against England. Then someone counters his point, mentioning Captain Benjamin Martin was bloodthirsty during the wilderness campaign.

This is the first mention of something that’s hinted at throughout the movie. Well, maybe not the first mention. The first is the opening scene where we saw the hatchet being put away and Mel Gibson’s voiceover talking about the sins of his past.

While the movie makes this a major plot point as if it’s something Benjamin Martin is trying to hide from his children, since the real Francis Marion didn’t have any children it’s obvious that’s not something he would’ve tried to hide from them. Since they didn’t exist.

But since the movie doesn’t ever really show what Benjamin Martin did during the wilderness campaign, as the film calls it, we can give the movie the benefit of the doubt and pretend like Benjamin Martin’s background is exactly the same as the real Francis Marion’s. So let’s take a moment to understand what they’re talking about by looking at history.

Before we do, though, it’s important to point out that Francis Marion’s military history is one that has received plenty of embellishment over the centuries. This is something that started long before The Patriot.

Many historians point to a man named Mason Locke Weems, commonly referred to as M.L. or Parson Weems, an author who lived from 1759 to 1825 who wrote The Life of General Francis Marion, which was the first biography on Francis when it was published in 1824.

In this biography, Parson Weems exaggerated plenty of facts.

As a little side note here, have you ever heard of the story about George Washington cutting down the cherry tree? That’s something Parson made up in a biography about George Washington. It’d seem he made up similar stories around Francis Marion, except there hasn’t been as much written about Francis Marion as there has about George Washington. So while the stories told by Parson Weems has helped to grow the legend of Francis Marion, at the same time it’s blurred many lines between facts and fiction over the years.

But not all such stories have been embellished. In particular, there’s a great biography written by William Gilmore Simms called The Life of Francis Marion that most historians agree is a much more accurate picture of Francis.

The real Francis Marion was born in Berkeley County, South Carolina as the youngest of six children. For some context, Berkeley County is just north of modern-day Charleston, South Carolina. In fact, if you visit Berkeley County today you’ll find much of it is covered by the Francis Marion National Forest.

We don’t know his exact date of birth, but most historians agree he was born at some point during the winter of 1732.

When he was born, Francis was very weak and often sick. In fact, according to some historians, his parents, Gabriel and Esther, didn’t think he would survive.

At only 15 years of age, Francis joined as one of seven crew on a ship bound for the West Indies. It never reached its destination, instead sinking after a whale rammed the ship. At least, that’s the story.

Francis and the other crew managed to survive adrift in a lifeboat in the ocean for an entire week. When they finally washed ashore, Francis decided he was done with open water.

For the next few years, Francis worked on his parent’s plantation in South Carolina until, around 1757 and at the age of 25, Francis joined the militia in South Carolina to fight in the French and Indian War.

The French and Indian War is what they’re referring to in the movie as the “wilderness campaign.” Despite its name, the French and Indian War was but one theater in the greater Seven Years’ War that took place between 1754 and 1763 and saw most of the world swept up in battle as it spread across Europe, the Americas, Asia and Africa.

The result of this war was one that saw the British Empire become one of the superpowers in the world while it effectively demolished France’s supremacy throughout Europe.

At that time, the American colonies were a part of the British Empire so the French and Indian War was named after the two enemies of the British during the vicious struggle against the British colonies in North America and the French colonies in North America, often referred to as New France.

On one side there was the French along with the Wabanaki Confederacy, an alliance of five Native American tribes. Throughout the war, they also allied themselves with six other Native American tribes. They were fighting against the British Americas, who had allied with another alliance of Native American tribes known as the Iroquois Confederacy. There were two other tribes who also allied with the British Americas throughout the war.

We don’t know specific numbers, but historians have estimated the French probably had somewhere around 10,000 troops at their peak. On the other hand, the British Americas had over four times that amount at their peak. So while a numbers advantage doesn’t always guarantee victory in war, it certainly helped.

Something else we don’t know is how many died directly at the hand of Francis Marion during the war, but of what we do know it’d seem Hollywood played up the brutality of it all. I’m not trying to imply that Francis wasn’t a violent person—it was a vicious and brutal war, after all.

But I think the professor of American history at Alabama’s Athens State University said it best when he stated, “One of the silliest things the movie did was to make Marion into an 18th century Rambo.”

If there was a time when Francis Marion’s brutality was at its height during the French and Indian War it was most likely near the end of the war. On June 13th, 1761, Francis was one of about 1,200 men under the command of Colonel Thomas Middleton that was involved in what would become the last major battle against the Cherokee tribe during the Battle of Etchoee.

It was during this battle that Francis started to notice how the Cherokee would use their knowledge of the terrain to ambush his men. These tactics would be the same he’d employ later—but that’s getting ahead of our story.

The battle began at about 8:00 AM and for a while the Cherokee had the upper hand. Slowly, and with heavy loss of life on both sides, the battle shifted until, at about 2:00 PM, the Cherokee were overrun.

It’s called the Battle of Etchoee because it was fought near a large Cherokee town called Etchoee. That town was burned to the ground during the bloodshed and the aftermath of this battle was a shatter to the morale of the Cherokee people.

For lack of a better way to phrase it, the Cherokee were all but finished. Their bravest warriors were lost, and those who remained didn’t stand a chance. After the Battle of Etchoee, the Carolinian militia had little to no resistance from the Cherokee nation as they ravaged fields, burned stores of grain and razed 14 other towns to the ground.

This bloody destruction of Cherokee towns filled with women and children was something that simultaneously helped earn Francis Marion’s reputation while filling him with sorrow for all the death he’d helped bring to so many.

We can start to get a sense for some of the sins that Mel Gibson’s character refers to.

Going back to the movie, Gabriel Martin signs up for the Continental Army and sends a letter home telling of his time in the Army. There’s no indication of how much time has passed, but in the letter Gabriel simply says that many seasons have come and gone. According to Heath Ledger’s voiceover, Charles Town has been captured by Cornwallis and things aren’t looking too great for the Americans.

Cornwallis is played by Tom Wilkinson in the movie.

Of course, we know Gabriel wasn’t a real person, but Cornwallis was.

And it’s because of his appearance in the movie around this point that we can get a general sense for how much time has passed.

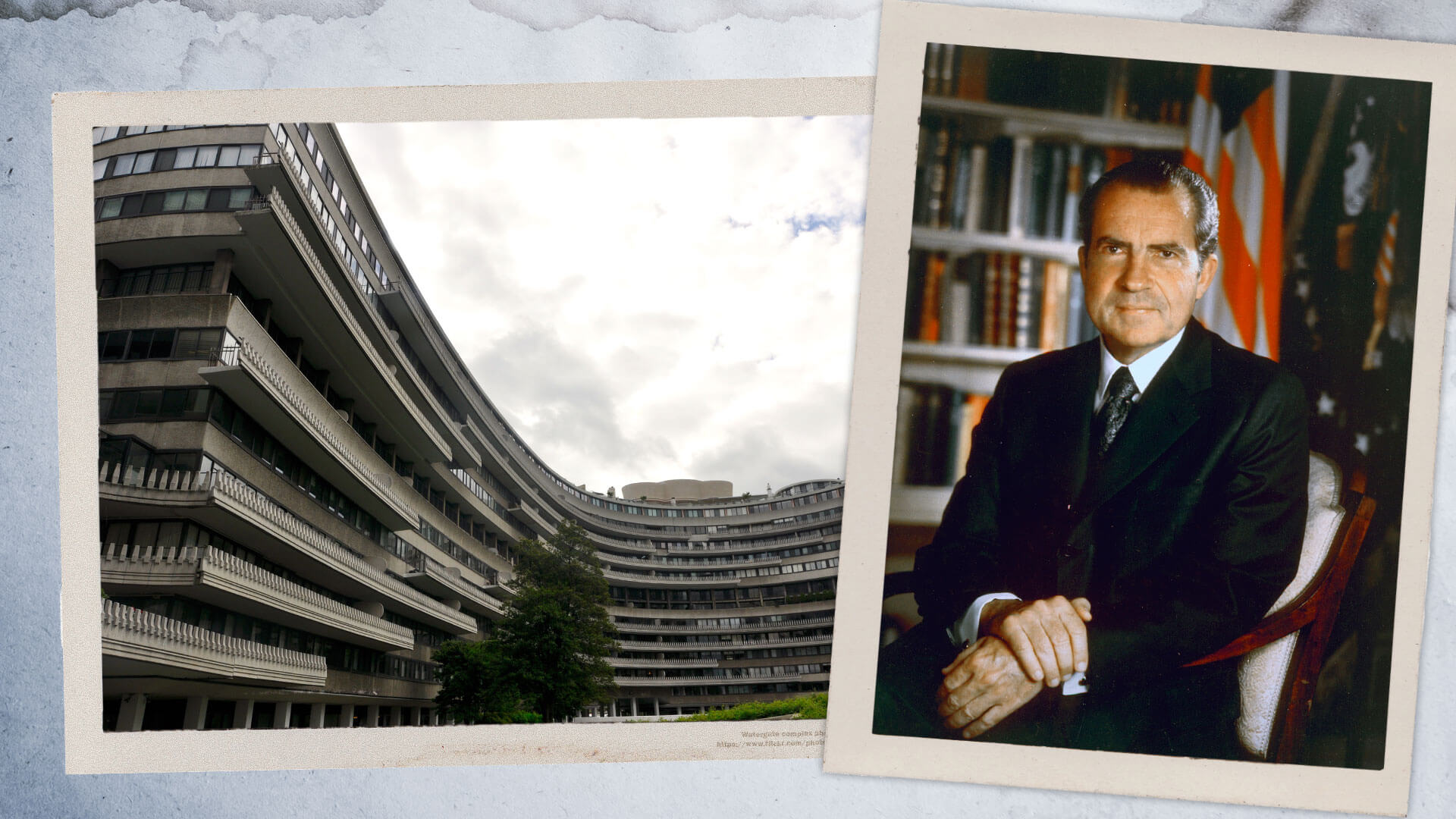

It was on May 12th, 1780 when the American Major General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered Charles Town unconditionally to the British after weeks of bombardments and siege.

That was a massive blow to the American cause as almost 7,000 troops surrendered to the British.

Although the movie doesn’t show this, General Lincoln didn’t surrender Charles Town to Cornwallis. Instead, at the time Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis was second in command to Lieutenant General Henry Clinton. So it was General Clinton that Charles Town was surrendered to.

However, after the surrender, Charles Town was left to Cornwallis while Clinton and his men left for New York on June 8th. So because the movie doesn’t ever really mention dates, maybe they just don’t show us Charles Town until after General Clinton has already left.

Back in the movie, there’s another major plot point that occurs when Benjamin Martin can hear the sounds of battle from his house. When a wounded soldier staggers into their home turns out to Gabriel, he ends up turning his home into a makeshift hospital to help both American and British soldiers injured in the battle.

That’s when we meet Colonel William Tavington, who’s played by Jason Isaacs. Colonel Tavington shows himself to be less than merciful when he orders all of the American troops be shot and the home burnt to the ground for helping the Continental Army. The last straw for Mel Gibson’s character is when Gregory Smith’s character, Benjamin Martin’s son Thomas Martin, dies in his father’s arms after being shot by Colonel Tavington.

With his home ablaze, one son murdered and another, Gabriel, being hauled off for treason, it’s the final straw for Benjamin Martin.

None of that is true.

We already learned that the real Francis Martin didn’t have any children and didn’t even marry until much after the war.

However, it’s worth pointing out that the character of Colonel Tavington was based on real person named Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. Probably the closest thing to reality between the fictional Colonel Tavington and the real Colonel Tarleton is that, just like we saw in the movie, Colonel Tarleton was the man ordered by General Cornwallis to hunt down Francis Marion.

In the movie, Jason Isaac’s version of Colonel Tavington is someone who does the most despicable things time and time again. Slowly but surely he becomes the epitome of the villainous character you absolutely loathe.

While the film certainly ratchets up the brutality quite a bit, the real Colonel Banastre Tarleton had a policy for killing Continental troops who surrendered. That policy earned the nickname “Bloody Ban the Butcher.”

But unlike Colonel Tavington, the real Colonel Tarleton never did things like herd people into a church to burn them alive. That was all added to help make you hate Colonel Tavington. And quite effectively, I might add.

According to the movie, Benjamin Martin snaps and exacts his vicious revenge after Thomas is murdered and his home burned. Then, after rescuing Gabriel, he joins up with the Continental Army and forms a militia. Operating out of the swamps of South Carolina, Benjamin Martin earns himself the nickname of “The Ghost” as he and his men use guerilla tactics against the British.

This goes on for quite a while in the movie and, well, quite honestly this whole vendetta between Colonel Tavington and Benjamin Martin is something that’s very much inflated and fictionalized.

There’s a very loose thread in reality here, but the filmmakers added in plenty of creative freedom from the real facts to essentially turn it into a whole new story.

Unlike Benjamin Martin in the movie, the real Francis Marion had been involved in the war nearly since it began. The Revolutionary War officially began on April 12th, 1775 and it was on June 21st, 1775 that Francis Marion was commissioned a captain in the South Carolina Regiment under the command of William Moultrie.

After the fall of Charles Town on May 12th, 1780, Francis Marion escaped capture more out of pure luck than anything. He had been involved in an accident just before the surrender, and had left the rest of the garrison, leaving the city to recover from his injuries. So when Charles Town surrendered, Francis wasn’t there.

It was after the town fell, a man named Thomas Sumter assembled a militia force. One of the men under Sumter’s command was Francis Marion.

He wasn’t under his command for long, because Thomas Sumter got injured and was forced to leave. Francis took over command of the militia, which consisted of less than 20 men, and started targeting British camps. Using the tactics he’d seen the Cherokee use decades before, Marion’s Men as they became known, would typically strike British forces around midnight when it was dark, cause some damage and chaos and then disappear into the night. They never did any major damage, but they were a nuisance.

Enough so that General Cornwallis ordered Colonel Banastre Tarleton to deal with the nuisance.

The nickname of “The Ghost” was one that some of the British soldiers gave to Benjamin Martin, but in truth that’s not the nickname Francis Marion had.

There were a few different instances where Colonel Tarleton almost caught Francis Marion. But Francis’ knowledge of the territory aided him, and let him slip away.

While the war raged on elsewhere, South Carolina was under British control. That meant, for the most part, Marion and his men were the only ones in the state who offered any resistance.

In November of 1780, Colonel Tarleton had gotten the whereabouts of Marion’s Men from a prisoner who had managed to escape Francis’ custody. For seven hours, Colonel Tarleton’s men tracked over 26 miles of swampland.

Finally, he gave up and remarked to one of his men, “As for this damned old fox, the Devil himself could not catch him.”

That’s how Francis Marion got the nickname of “Swamp Fox.”

After months of struggles, the Continental Army returned to South Carolina and Francis Marion joined back up with them.

As a side note, one of the characters that we haven’t really talked about yet is the French liaison Jean Villeneuve, who’s played by Tcheky Karyo in the movie.

The history of Benjamin’s brutality in the French and Indian War was something that brought tension on screen.

There’s a very little bit of history here, even though the character of Jean Villeneuve is a fictional person. But the French did help the Americans fight against the British during the Revolutionary War.

For example, men like Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, or Baron von Steuben as he’s often referred to, served in the American Continental Army and helped train and fight alongside American militia.

Or there was Marquis de Lafayette, who was a key player in the French Revolution, and also fought in the American Revolution alongside the Continental Army.

Back in the movie, the big fight at the end finally takes place and we see what we’ve been waiting for throughout the entire movie—the end of the hated Colonel Tavington.

Of course, the struggle between the fictional Benjamin Martin and the fictional Colonel Tavington was, well, fictional. But even though the movie doesn’t give many specifics, it’s safe to assume the movie is basing this battle on the defeat of the character that Colonel Tavington is based on, Colonel Tarleton.

That was the Battle of Cowpens, although it didn’t go down like we saw in the movie.

In truth, the battle began after American Brigadier General Daniel Morgan led his 970 troops toward a British fort that they intended on capturing. General Cornwallis ordered Colonel Tarleton lead his 1,200 troops to meet General Morgan.

On January 17th, 1781, the two forces met at what we now know as the Battle of Cowpens. So while Colonel Tarleton was there, Francis Marion was not.

We know this because of a letter that Major General Nathanial Greene sent to Francis Marion on January 18th informing him of Colonel Tavington’s defeat:

On the 17th at daybreak, the enemy, consisting of eleven hundred and fifty British troops and fifty militia, attacked General Morgan, who was at the Cowpens, between Pacolet and Broad rivers, with 290 infantry, eighty cavalry and about six hundred militia.

The action lasted fifty minutes and was remarkably severe. Our brave troops charged the enemy with bayonets and entirely routed them, killing nearly one hundred and fifty, wounding upwards of two hundred, and taking more than five hundred prisoners, exclusive of the prisoners with two pieces of artillery, thirty-five wagons, upwards of one hundred dragoon horses, and with the loss of only ten men killed and fifty-five wounded.

Our intrepid party pursued the enemy upwards of twenty miles. About thirty commissioned officers are among the prisoners. Col. Tarleton had his horse killed and was wounded, but made his escape with two hundred of his troops.

So what was Francis Marion up to?

Just a few days after the defeat of Colonel Tarleton, on January 24th, 1781, General “Light-Horse Harry” Lee and Francis Marion’s men teamed up to attack the 200 British soldiers defending Georgetown, South Carolina.

For some context here, the Battle of Cowpens took place near the modern-day city of Chesnee, South Carolina. That’s about two miles, or about 3.2 kilometers to the south of the border between North Carolina and South Carolina.

Meanwhile, Georgetown, South Carolina is about 192 miles, or 310 kilometers, to the south of Chesnee.

Francis and his men continued aiding the Continental Army in their attempts to push the British out of South Carolina.

Back in the movie, when Tom Wilkinson’s version of General Cornwallis orders retreat at the Battle of Cowpens, it’s implied to be pretty much the end of the war.

That’s not true, nor was it the end of the war for Francis Marion.

Another major battle for Francis was the battle of Eutaw Springs.

For a bit of context, that battle took place near the modern-day city of Eutawville, South Carolina, which is a tiny town north of Charleston near the lake now named Lake Marion, after Francis, and Lake Moultrie, named after Francis Marion’s commanding officer when he first joined the Continental Army.

At about 4:00 AM on September 8th, 1781, somewhere between 2,200 and 2,600 American troops under the command of Major General Nathanial Greene began marching along the Santee River toward Eutaw Springs. One of the men under General Greene’s command was the now-Brigadier General Francis Marion who had about 40 cavalry and 200 infantry under his command.

Four hours after they started their march, they came across some Tori cavalry under the command of Captain John Coffin.

Oh, and the term Tori was something the Americans called Loyalists—or Americans who were still loyal to the British Crown. So they were Americans who were fighting the Colonialists alongside the British troops.

Anyway, Captain Coffin’s men tried to capture a scouting party but instead were ambushed by “Light-Horse Harry” Lee’s men, leading to the capture of 40 cavalry. Then an additional 400 British troops were captured when the American forces happened upon troops foraging in the woods for supplies.

This severely depleted the men under the command of Major General Alexander Stewart. The remaining 1,600 or so men met up with the bulk of the American force and battle ensued. It was a battle that lasted a full day and ended in what many consider a stalemate.

None of that is mentioned in the movie, of course, but it’s important because the Battle of Eutaw Springs was one of the last major battles fought outside of Charles Town.

Some argue that tactically, the British won because it was the Americans who were forced to withdraw from the battle. And yet others argue that strategically, the Americans won because the British forces were so battered after the battle that they would later retreat to Charles Town.

This time it was the Americans who would lay siege to Charles Town, trapping the British troops inside and effectively removing them from the war.

At the very end of the movie, after the battle where Benjamin Martin gets his revenge on Colonel Tavington, we hear Mel Gibson’s voiceover that explains the rest of the war.

According to the movie, General Cornwallis fled the battlefield and went north. Benjamin and the other Americans followed until Cornwallis holed up in Yorktown, Virginia.

Then we see text on screen that says it’s Yorktown, 1781 as Mel Gibson’s voiceover continues to explain that they met up with George Washington’s forces from the north, surrounding Cornwallis at Yorktown, who himself couldn’t escape to the seas because the French had finally arrived.

By now it shouldn’t come as much of surprise that a lot of that was made up, but it is true that General Cornwallis ended up in Yorktown, Virginia in 1781.

It was a siege that started on September 29th and, just like the movie says, was helped by General Washington’s troops by land and the French Navy who had arrived and blocked Cornwallis’ exit via the sea.

The siege continued until, on the morning of October 17th, two men came out of Yorktown waving a white handkerchief. American bombardment of Yorktown stopped and the men were led behind American lines where surrender was discussed.

Negotiations continued until two days later when, on October 19th, 1781, the Battle of Yorktown officially came to an end when the British signed articles of capitulation.

There were four men who signed the surrender. For the Americans it was General George Washington along with Rochambeau from the French Navy. For the British it was General Cornwallis and Captain Thomas Symonds of the Royal Navy.

Thus marked the end of the Siege of Yorktown and with it, the final major battle of the American Revolutionary War.

Back in the movie, there’s a brief moment where Benjamin Martin says goodbye to Colonel Burwell, who says his wife has had their son. They named him Gabriel.

We already know Chris Cooper’s Colonel Harry Burwell is a fictional character. But what of the man Colonel Burwell is based on, Major General “Light-Horse Harry” Lee?

Well, it’s true that Major General Henry Lee had children. Nine of them, in fact. None of them were named Gabriel. His oldest son’s name was Philip Lee who was born in 1784, three years after the Siege of Yorktown.

But you’ve probably heard of one of his children. His second-youngest child, Robert, would grow up to become the General Robert E. Lee who was in charge of the entire Confederate Army during the Civil War.

The final scene in the movie shows Benjamin Martin himself return to Charlotte and the remainder of his children. When he does, they arrive back at their plantation and begin rebuilding it.

That’s not too far off from what happened to Francis Marion, albeit without the children.

On September 3rd, 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed by representatives of King George III of Great Britain and the United States of America. There was a lot included in the Treaty of Paris, but today, Article I is the only piece that remains in effect—that article being the portion that is the legal existence of the United States as a sovereign country.

As for Francis Marion, after the end of the war, he returned to his plantation in South Carolina to find it had been burned to the ground at some point while he was away. All of the slaves he had owned that were maintaining the plantation had run away to fight for the British.

He didn’t have any money, so he had to borrow funds to buy more slaves and rebuild his plantation—that’s certainly something the movie fails to recognize as it implies Benjamin Martin has servants working as free men and women. Not really the case with the real Francis Marion.

As we learned earlier, Francis was married Mary Esther Videau on April 20th, 1786. The two never had children, but Francis would go on to serve in the South Carolina State Senate before retiring to his home to live out the rest of his days in peace. On February 27th, 1795, Francis Marion passed away on his plantation at the age of 63.

Almost 38 years later, on January 15th, 1833, Colonel Banastre Tarleton, died at the age of 78 in his home in Leintwardine, England.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)