In this episode, we’ll learn about historical events that happened this week in history as they were depicted in these movies: Silkwood, Young Winston, and Saving Lincoln.

Events from This Week in History

Birthdays from This Week in History

Movies Released This Week in History

Mentioned in This Episode:

- GAO Report on Kerr-McGee: https://www.gao.gov/assets/red-75-374.pdf

- The Oklahoman Article about Silkwood: https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/1983/12/15/silkwoods-boyfriend-likes-film/62820840007/

- Photographs of the Gettysburg Address: https://www.cnn.com/2013/11/18/us/gallery/gettysburg-address/index.html

Did you enjoy this episode? Help support the next one!

Disclaimer: Dan LeFebvre and/or Based on a True Story may earn commissions from qualifying purchases through our links on this page.

Transcript

Note: This transcript is automatically generated. There will be mistakes, so please don’t use them for quotes. It is provided for reference use to find things better in the audio.

November 13th, 1974. Oklahoma.

We’re in a bedroom. The walls are empty, and light is streaming through a window covered by a Confederate battle flag. A man is in the bed, sleeping, but he’s quickly woken up by an alarm going off. As he rouses, we can see it’s Kurt Russell’s character, Drew Stephens.

A woman rushes into the room from the left side of the frame. This is Meryl Streep’s character, Karen Silkwood. Karen apologizes to Drew, saying she forgot to turn off the alarm. He doesn’t seem to care about that but can tell that Karen is already dressed in a leather jacket and black jeans. It looks like she’s about to leave. He just says that he thought she wasn’t going in—it seems like he already knows that she’s going into work.

Sitting on the end of the bed to put her boots on, she tells him that she has to go in.

He rolls over, burying his face in the pillow, and tells her to call in sick.

She says no, and he tries to get her to call in sick again. Again, she says she can’t call in sick. This time she gives a reason, though, because she has to get something from work. He keeps asking her questions as she puts her purse over her right shoulder and opens the door of the small apartment.

She closes the door behind her, walking down the stairs just outside the front door in a rush. By the time she reaches the bottom of the stairs, Drew comes through the door. Shirtless, he’s buttoning his jeans as he tells her not to get anything from the plant. She asks him to do her a favor and pick up Paul Stone and the guy from the New York Times at the airport if she gets hung up at the union meeting.

“Fuck no,” he says.

She pleads, saying she doesn’t know how long the meeting will go tonight. He’s defiant, saying he doesn’t want her doing that. But, she’s doing it anyway. She smiles as she says this.

Drew reminds her that she doesn’t owe the union anything. She doesn’t owe the New York Times anything. She diffuses the situation, let’s not fight. He smiles back, agreeing, and she makes her way to her small car. He watches from the top of the stairs as she backs out of the dirt parking lot and drives away.

As her car drives off, the movie starts playing the song “Amazing Grace.”

The song continues to play as the next shot shifts to nighttime. Karen is leaving a small diner that has a sign that says Crescent Café, and “Just good food,” outlined with a red, neon light.

She’s carrying a folio of some sort in her hand, and just as she’s about to reach her car another woman catches up with her. We can hear the other woman asking Karen for her notes. She hands over some papers, and the woman asks if Karen is okay. Karen assures her that she is and the two women say goodbye to each other as Karen gets in her car.

The song keeps singing, “I once was lost, but now I’m found.”

The camera cuts to Karen driving her car. The view is through the windshield and since it’s nighttime in the Oklahoma countryside, there aren’t any streetlights. Basically, it’s pitch-black outside and all around the dim light that lets us see Karen’s face as she’s driving her car.

The song continues, “’twas grace that taught my heart to fear, and grace my fears relieved.”

The pitch-black outside is pierced by the headlights of a vehicle behind Karen’s car. She doesn’t pay attention to it at first, it is a road after all. But as the car gets closer the lights get brighter. It’s obviously causing her some difficulty seeing as the headlights bounce off her rear-view mirror, because now she’s holding her hand up to block out the bright light.

“Through many dangers, toils, and snares.”

The song keeps playing as the camera zooms into the headlights until the whole screen goes white before fading to black.

When the movie comes back, the song is still playing as we see the scene of Karen’s car destroyed after what looks like a terrible accident. It’s off the side of the road in a ditch with steam pouring out, and some piece—maybe a door or something—sitting off to the side. The driver’s side window is missing, and Karen is hanging partially out of the car, motionless.

The true story behind this week’s event depicted in the movie Silkwood

That sequence comes from the 1983 biographical film that has Karen’s last name: Silkwood. The event it’s depicting is something that happened this week in history when Karen Silkwood died under suspicious circumstances on November 17th, 1974.

Of course, we don’t really get what’s so suspicious about the death from the part of the movie that I just explained. That’s because what made it suspicious didn’t necessarily happen this week in history, so let’s learn a bit more about the true story.

Karen Silkwood was a lab tech who worked at a company called Kerr-McGee. They were an energy company involved in everything from oil, natural gas, as well as uranium mining. I say “were” in the past tense because even though the company was founded in 1929, Kerr-McGee was bought out by a company called Anadarko Petroleum in 2006. Then, in 2019, Anadarko was bought out by Occidental Petroleum, so as of today most of what used to be Kerr-McGee is run by Occidental.

But that’s outside the scope of our story today.

Back in 1974, Kerr-McGee had been around for about 45 years, so they had a lot of locations around the world, but headquarters were in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. About 35 miles or 55 kilometers to the north of Oklahoma City, Kerr-McGee had a plutonium plant near the tiny town of Cimarron City. It was officially called the Kerr-McGee Cimarron Fuel Fabrication Site.

That’s where Karen Silkwood worked as a lab tech.

In the movie, we see the Crescent Café and Crescent is the name of a city in Oklahoma which is only a couple miles, roughly three kilometers, north of Cimarron City. So, it’s not too far for Karen or any other workers at the Kerr-McGee plant to visit.

Something else we see in the movie is the mention of a union meeting that Karen is going to, and it is true that Karen was involved in the union.

She was hired at the plant in 1972, and she almost immediately joined the Oil, Chemical & Atomic Workers Union. As part of the union, she took part in a strike that happened at the plant. But then, once the strike was over, she was assigned to health and safety issues at the plant. In that role, she found what she thought were a number of violations.

But here’s where things start to get murky, because we don’t really know everything that happened near the end of Karen’s life.

It’s normal to be tested for radioactive contamination when you’re working at a nuclear fuel facility, but it was a surprise to many when Karen came back positive for plutonium contamination on multiple occasions. She’d testified to the Atomic Energy Commission in 1974 that her contamination was the result of safety standards slipping at the plant.

But teams at Kerr-McGee looked at the gloves that she thought was the reason she’d been contaminated, but they didn’t find a leak in the gloves.

Soon after, on November 7th, 1974, more parts of Karen’s body were found to be contaminated. On top of that, parts of her apartment at home were also found to be contaminated. How could that happen? Some have suggested perhaps Karen took plutonium home on purpose to contaminate herself and the apartment. Why? Maybe to prove her point that the plant wasn’t safe.

I found some conflicting reports in my research about what happened on November 13th, 1974.

Some say she was at a union meeting after a normal day at work, which would seem to suggest the movie was correct when mentioning the union meeting might run late. Others say it wasn’t a union meeting, but rather that she was planning a nighttime meeting with a reporter from the New York Times to give the proof about the safety issues at the plant. Still others say it was both; that she went to a union meeting and then was planning to meet up with the New York Times reporter afterward.

Regardless of the union meeting or not, as the story goes, she was on her way to meeting the New York Times reporter on the evening of November 13th when she crashed her car into a concrete sewer drain crossing under the road along Highway 74 in rural Oklahoma. She died before help arrived at the scene, and no documents or evidence was found.

Did someone run her off the road and take the evidence? That’s the question.

An autopsy revealed she’d consumed a large number of drugs, some reports say they were Quaaludes, that made her fall asleep at the wheel. But others reported that the rear bumper of her car had marks on it to suggest another car had hit her and run her off the road.

The next year, in 1975, the Comptroller General of the United States released a report entitled: Federal Investigations Into Certain Health, Safety, Quality Control, and Criminal Allegations At Kerr-McGee Nuclear Corporation.

I’ll include a link to that report in the show notes for this episode if you want to read it, but here is a quote from the report:

On November 13, 1974, Karen was killed in an automobile enroute to a meeting where, Silkwood crash according to the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers International Union, she was to provide evidence she had collected on the allegations. Regulatory Commission inspectors made radiological surveys of the automobile, personal effects, and site of the crash and found no contamination. One inspector noticed some papers in the automobile, which had been removed from the accident site, but was unable to describe their contents. The Regulatory Commission lacked the authority to retain the papers. The car and its contents were released to Karen Silkwood’s boyfriend.

According to the union, the released possessions contained papers but did not include all the documents related to health and safety hazards and falsification of quality control records. No papers were found at the accident site. Because of possible Bureau investigation into this allegation, GAO did not pursue this matter further.

For a little context to that, GAO is the General Accounting Office while the mention of Karen’s boyfriend is the guy played by Kurt Russell in the movie—Drew Stephens. In a 1983 article from newspaper, the real Drew Stephens said he was “very pleased with the movie,” although he admitted, “I’ve come to accept the fact that I may never know what really did occur.”

Also mentioned in the article, Kerr-McGee’s official reaction was that the movie is nothing more than “a highly fictionalized Hollywood dramatization.”

I’ll link that in the show notes, too, you can read that article more if you want to see what was said about the movie.

But, if you want to watch the movie that portrays the event that happened this week in history, check out the 1983 movie simply called Silkwood. We started our segment at about 2 hours and 3 minutes into the movie.

November 15th, 1899. Natal, South Africa.

We’re riding on an armored train. Voiceover tells us that Captain Alymer Haldane invited me to go on reconnaissance with him. As we hear this voiceover, we can see the younger version of the person giving the voiceover: Winston Churchill. He’s played by Simon Ward in the movie while Captain Haldane is played by Edward Woodward.

The train arrives at a station near a sign that says “Chieveley,” and squeals to a stop. Churchill asks Haldane if they’re going back, to which Haldane replies that this is as far as our orders take us. Looking around, Haldane remarks that everything is quiet. So, yeah, they’re going back. The train whistle blows as it starts moving again, this time going back the way they came.

The camera shifts to an angle where we can see the train leaving the station and going back into the green countryside. Haldane was right, everything is quiet. Nothing to be seen but the grassy hills in the distance against a cloudy sky.

As the train picks up speed, Haldane keeps his eyes glued to his binoculars. Everything is quiet, but this is reconnaissance, after all. Churchill relaxes in the corner of the train car along with some other soldiers. Churchill strikes up a conversation with Haldane. Behind the men we can see ruins of stone buildings the train is passing by.

Just then, the sound of something whistling through the sky. Haldane looks up in alarm, “Down!” He yells. An explosion hits just by the train. Gunfire starts as the British soldiers in the train start shooting at the soldiers who are appearing over the green hills. Churchill looks over the side of the train to see that they’re rolling up more artillery, too.

In the next shot, we can see a number of artillery rounds blowing up around the armored train as it tries to escape the ambush. The soldiers inside are shooting out holes in the sides, and for a moment it seems like the train might be able to escape the attackers’ position behind.

Then, the camera cuts to the engine when the engineer driving the train notices something: Rocks on the tracks. They must have been placed there in the time it took the train to get to Chieveley and come back. He yells for the brakes, but it’s too late. The train crashes into the rocks, derailing some of the cars, scattering soldiers on the ground beside the tracks.

This fight isn’t over yet. The ambushers on the ridge appear again, continuing to shoot at the now stopped train.

Churchill yells to Haldane, letting him know they’ve been derailed. Then, with Haldane’s blessing, he runs to the front of the train to see what he can do. Assessing the situation, Churchill convinces the engineer to try and get the engine to run again. But it won’t do much good with the tracks still blocked. The rocks aren’t there anymore, but rather blocked by a train car that’s derailed and thereby blocking the tracks after the crash.

Churchill gets help from some of the other soldiers as they push the derailed car off the tracks, all the while being shot at by the soldiers from the ridge. Amazingly so, it’s a success! With the tracks cleared, the engineer can start moving the train along the tracks again.

They pile the wounded soldiers on the engine and the healthy soldiers run behind the engine as cover. Things get worse, though, when the brakes go out on the train just as there’s a downgrade in the terrain so not all the soldiers can keep up with it. By the time they’re able to stop the train, Churchill goes back on his own to get some of the soldiers left behind—only to be captured along with Haldane and the other soldiers who couldn’t keep up with the train.

The true story behind this week’s event depicted in the movie Young Winston

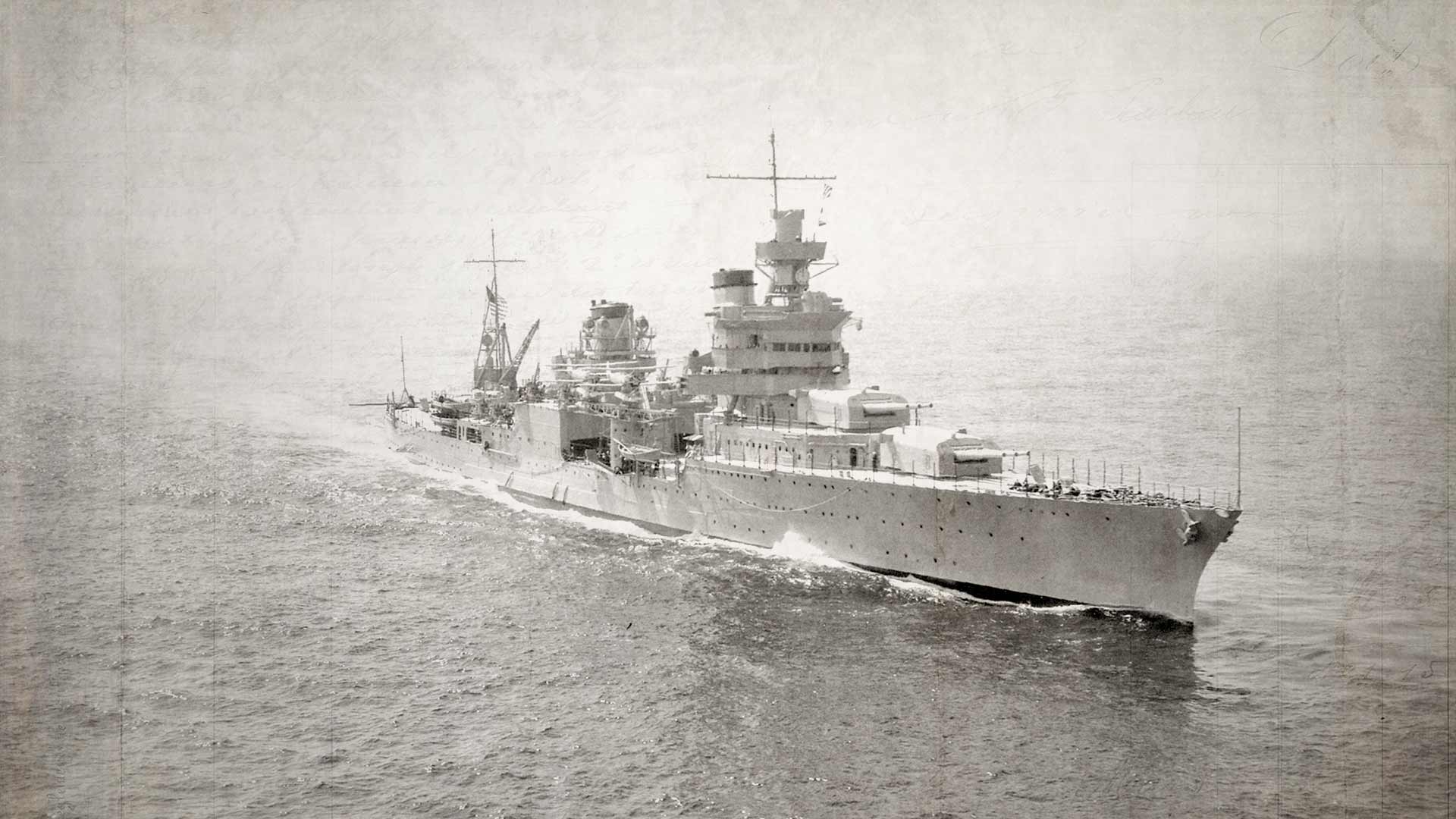

That sequence comes from 1972 movie called Young Winston. The event it’s depicting is when Winston Churchill was captured during the Boer War, which happened this week in history on November 15th, 1899.

To find out how well the movie showed this, let’s go back to a previous episode of Based on a True Story when I had a chat about this event with Dr. J. Furman Daniel, author of a forthcoming book called Mud, Blood, and Oil Paint: The Remarkable Year that Made Winston Churchill. Here’s what Furman had to say about this event:

It has to simplify the shootout with the train. And what he was doing down in South Africa a little bit, and it has to simplify his capture and his transfer to the prison and his escape, but overall, it does a pretty good job. I think that the script writers and the directors do a pretty good, make a pretty good set of choices of what do we leave in?

What do we leave out and keep that narrative moving? I think it does a pretty good job and is generally consistent with the historical evidence there as well, at least in, in the case of the train shootout and his capture. We don’t have to just take Churchill’s work. There were lots of eyewitnesses that attest to Churchill’s bravery.

The fact that he went above and beyond the, he wasn’t even technically a combatant and yet he put himself in this position of. The danger when he did not have to, it does a good job of making that an interesting scene with a train shootout, almost a Wild West feel to certain parts of it.

It does a good job of that quickly moving that along while telling the story in a pretty accurate way as well.

After that, Furman went on to explain how well the movie portrayed the next part of the movie—which is Winston Churchill escaping from prison after being captured. But that happened in December of 1899, so if you want to see the event that happened this week in history as it’s depicted on screen, check out the 1972 film called Young Winston. We started our segment at about an hour and 42 minutes into the movie.

And if you can’t wait until December to hear how Churchill escaped, scroll back to episode number #259 of Based on a True Story to hear where Furman explains how well the movie depicted Churchill’s escape. Oh, and look for Furman to come back on the podcast to chat about Churchill during World War II soon!

November 19, 1863. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

We’re outside, among a crowd of people. Maybe four or five rows into the audience as we’re all facing the stage. Behind the stage it looks like there’s trees and a few buildings off in the distance. The focus—everyone’s focus—is the stage itself. There are ten men seated on the stage; everyone is wearing black suits, ties, and tall hats. The man in the center stands up, addressing the crowd.

In a bold voice, he announces: “The President of the United States!”

Then, he turns around as the man just to his left—which looks like our right side since we’re facing him—stands up. Everyone claps and the movie gives us text on screen letting us know it’s Gettysburg, PA in the year 1863.

The two men shake hands. The President then takes off his hat, handing it to the other man. The camera cuts to the audience, a sea of faces watching as the President addresses them.

There’s some voiceover here, which explains the president has to explain why this plague of war must continue. The camera cuts back to the President on stage, and we can see his face more clearly now. It’s Abraham Lincoln, who is played by Tom Amandes in the movie.

The voiceover stops as President Lincoln begins to speak:

Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation…

The true story behind this week’s event depicted in the movie Saving Lincoln

That sequence comes from the 2013 movie called Saving Lincoln. I’m sure you’re already familiar with what it’s depicting since it’s one of the most popular speeches ever given by a U.S. President: The Gettysburg Address, which President Lincoln gave this week in history on November 19th, 1863.

With that said, the movie’s depiction of the Gettysburg Address has to be dramatized quite a bit because the true story is that we just don’t know exactly how Lincoln delivered it. Remember this was 1863, and we don’t have footage of the speech. We certainly don’t have footage with audio.

There are a limited number of photos of the Gettysburg Address, and only one where we can see Lincoln himself. I’ll include a link in the show notes to the photo if you want to see it, but right away you can tell it looks different than what we see in the movie with the number of men to either side and behind Lincoln—although it does show Lincoln without his top hat, so the movie got that right.

How do we know what Lincoln said, then? Well, that comes from the five known manuscripts of the speech that Lincoln gave to different people. They’re now known as the Nicolay draft, the Hay draft, the Everett copy, the Bancroft copy, and the Bliss copy. They’re named after the people that Lincoln sent versions to. Of these five copies, probably the best-known is the Bliss copy, named after Colonel Alexander Bliss. It was given to Bliss to include in a book called Autograph Leaves of our Country’s Authors.

That book was published in 1864, making it the final version of the address that Lincoln gave out. But the primary reason the Bliss copy is used most is because it’s the only copy to include a title as well as being signed and dated by President Lincoln. The Bliss copy is what’s inscribed on the south wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

With all that said, here is the full version of the Gettysburg Address:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives, that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate ~ we can not consecrate ~ we can not hallow, this ground. The brave men living and dead who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us ~ that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion ~ that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain ~ that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom ~ and that government of the people by the people for the people shall not perish from the earth.

If you want to watch the movie’s depiction of Lincoln giving the Gettysburg Address as it happened this week in history, check out the 2013 movie called Saving Lincoln. The Gettysburg Address starts at about 58 minutes and 31 seconds into the movie.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)