On this episode, we’ll learn about historical events that happened this week in history as they were depicted in The Alamo, Selma and Malcolm X.

Did you enjoy this episode? Help support the next one!

Disclaimer: Dan LeFebvre and/or Based on a True Story may earn commissions from qualifying purchases through our links on this page.

Transcript

Note: This transcript is automatically generated. There will be mistakes, so please don’t use them for quotes. It is provided for reference use to find things better in the audio.

March 6th, 1836. Texas.

It’s the early morning hours. So early that the sun hasn’t even started to peek over the horizon, leaving the screen nearly pitch black. We can hear some sounds of soldiers moving, although it’s hard to see them very well because it’s so dark.

We can see a soldier stab someone in the neck with a bayonet, making it so he can’t scream as he dies.

In the next shot we see Billy Bob Thornton’s version of Davy Crockett plucking at an instrument. Then, he seems to have heard something—maybe the noise of the man dying—but he doesn’t make any indication of what it was.

But, it was something.

Crockett stands up and looks over the wooden wall he was sitting right next to. On the other side he can see movement. Instantly, he ducks back down so he’s not seen. Then, without pausing, he stands back up and aims his rifle.

BANG!

All of a sudden, countless Mexican soldiers start yelling “Viva Santa Anna!” as they rush forward. Inside the walls, the noise has woken everyone up. Defenders take their places behind the walls and a huge battle ensues.

This depiction comes from the 2004 movie called The Alamo and it shows us an event that happened this week in history: The final assault on the Alamo that ended the 13-day siege.

The true story is a little more difficult to give absolute facts about the smaller details like who fired the first shot, because the truth is that the final assault on the Alamo wasn’t very well documented. On top of that, everyone who was defending the Alamo died.

That’s not to say everyone died inside the Alamo, there were a few noncombatants—women and children, mostly—who survived. But, the death of the defenders makes it even more difficult to know exactly what happened in the hours and even days leading up to the final assault.

Was the famous Davy Crockett the first one to shoot early that morning like we see in the movie? We don’t know. But, realistically, it’s probably doubtful.

He did die there, though. But even his death is something we’re unsure of exactly how it happened. Some claimed to see his body among the other defenders while some say he was one of a few prisoners captured by General Santa Anna who was executed after the battle ended.

What we do know is that there were 187 men who died at the Alamo and about 3,000 Mexicans involved in the final assault. When Santa Anna’s soldiers arrived there were about 5,000 men—1,544 of them died during the 13-day siege.

Davy Crockett was just one of 133 defenders from the United States who died at the Alamo. There were 41 from Europe and 13 native Texans.

When I say native Texans, that’s something important to keep in mind because this happened in 1836, and Texas wasn’t even a part of the United States at that time in history. In fact, it was in part because of what happened at the Alamo that helped Sam Houston end up winning the overall war because even though it was a defeat, it helped motivate Houston’s soldiers into forcing Santa Anna to concede Texas. Then, in 1845, the United States annexed Texas—which kicked off a new war between the United States and Mexico that started in April of 1846 and lasted until February of 1848.

If you want to watch the event that happened this week in history, though, check out the 2004 movie The Alamo. The final assault on the Alamo starts at an hour and 35 minutes into the movie.

And if you want to learn more about the true story, we covered that movie on episode #172 of Based on a True Story.

March 7, 1965. Selma, Alabama.

There’s a line of people walking down the street. We can see they’re all dressed nicely as the camera pans up from polished shoes to suits for the men and nice dresses for the women.

We can hear a reporter’s voiceover, John Lavelle’s version of Roy Reed, explaining the scene as we see it unfold on screen.

About 525 Black men and women left Brown’s chapel and walked six blocks to cross Pettus Bridge and the Alabama River.

After a brief pause, Wendell Pierce’s version of Reverend Hosea Williams looks to Stephan James’ version of John Lewis standing alongside him at the front of the line of people. Lewis looks back at Williams. Then, after a subtle nod, they continue walking.

Everyone follows.

Reed continues to explain the event from a phone booth where we can assume he’s calling the newsroom back at the paper. He says they were young and old, carrying an assortment of packs, bed rolls and lunch sacks.

Then, we can see exactly that. Men and women of all ages carrying packs, bed rolls and lunch sacks as they walk across a street corner.

We can see a big bridge spanning a river. This must be the Pettus Bridge and the Alabama River that Reed mentioned earlier.

As the Black men and women cross the bridge, Reed’s voiceover picks back up again as he talks about troopers. Just then, we can see a line of police officers—all of them white—standing in a line. Reed explains the troopers were waiting 300 yards beyond the end of the bridge. There were the troopers, dozens of posse men, 15 of them on horses and at least 100 white spectators, many of whom are holding Confederate flags.

The Black men and women cross the bridge and approach the troopers.

Then, the camera cuts to David Oyelowo’s version of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Someone calls and tells them to turn on the TV.

They turn on the TV just in time to see a special news bulletin.

The camera cuts back to the bridge where we can see the face-off between the troops and the people peacefully crossing the bridge. One of the troopers pulls out a megaphone and tells the crowd they have to disperse. The march will not continue.

Reverend Williams asks for a word with the Major in charge of the troopers. They refuse, there’s nothing to talk about. John Lewis asks again to speak with Major Cloud.

Michael Papajohn’s version of Major Cloud replies by giving a nod to the troopers, who all put on gas masks. Then, he orders them to advance and the troopers rush the crowd.

What follows is mayhem. Troopers beating innocent men and women in what ends up being a scene mixed with tear gas and blood.

This brutal depiction comes from the 2014 movie called Selma and it shows a very real event that happened on March 7th, 1965 in Selma, Alabama. While the movie’s portrayal is well done from a historical perspective, there is more to the story.

There were 300 protesters who started from Brown Chapel in Selma, Alabama at 3 PM on Sunday, March 7th, 1965. The reason why so many of the protesters were carrying lunch packs, sleeping bags and things like that was because the original plan was to march the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery. That’s the capital of Alabama, and once there the protesters planned to hold a rally on the steps of the state capitol.

But they never made it the 54 miles—instead, they made it a little over a mile to the Edmund Pettus Bridge that spans the Alabama River.

That’s where, just like we see in the movie, a bunch of Alabama State Troopers along with some vigilantes who were all under the command of Major John Cloud blocked the way. And just like we see in the movie, Major Cloud refused to speak to the protestors and, after ordering them to disperse, ordered gas thrown into the crowd. Then, they used force—clubs and other weapons to beat the protestors until they all fled back to Selma.

While the event wasn’t broadcast live like the movie makes it seem, it was filmed and broadcast later—the images from the event we now know as “Bloody Sunday” were etched into history and helped in the campaign for passing the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

If you want to watch the event that happened this week in history, check out the 2014 movie called Selma, the march across the bridge happens at about an hour and 10 minutes into the movie.

And if you want to learn more about the true story, we covered that movie on episode #167 of Based on a True Story.

New York City.

We’re at a press conference.

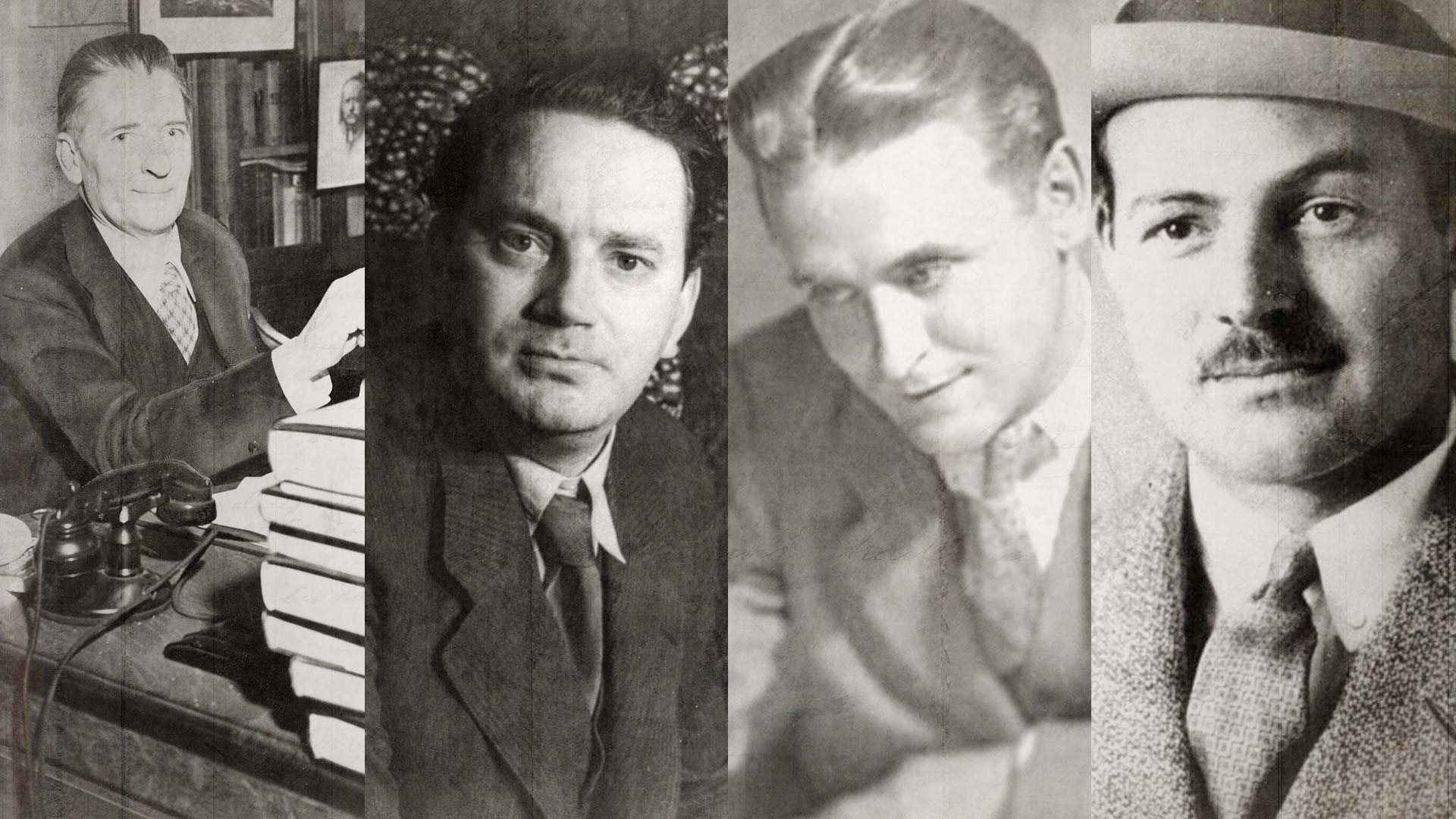

There are four people sitting at a table, three men and one woman. Behind them stands three other men—if I had to guess those men standing in the back are bodyguards.

At least seven mics are facing Denzel Washington’s version of Malcolm X, who is sitting in the center of the table.

The footage starts in black and white, but then switches to color when the camera angle changes to showing the audience listening.

Malcolm goes on to say this press conference is to help clarify his position.

He doesn’t waste any time to mention exactly what he means by that: Internal differences within the Nation of Islam have forced him out of it.

He says that he used to start everything with “The Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us” and so on, but now he says that day is over. From now on, he speaks his own words and thinks his own thoughts.

This depiction comes from the 1992 biopic called Malcolm X and it shows a very real press conference that took place on March 12th, 1964.

Although in the true story, while he did mention Mr. Muhammad in the speech, Malcolm didn’t talk about how he used to start his teachings with “The Honorable Elijah Muhammad teaches us” and so on.

He did say:

Internal differences within the Nation of Islam forced me out of it. I did not leave of my own free will. But now that it has happened, I intend to make the most of it.

So, that message was a little different than what we see in the movie…but the basic concept is the same. And it’s an important historical event because this press conference and the actual day that Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam, which was also this week in history on March 8th, 1964. That was for the reason the movie correctly showed in a scene a little earlier in the movie, after Malcolm X called the JFK assassination an example of “the chickens coming home to roost” the National of Islam suspended him for 90 days.

So, he left, and the press conference…well…let’s just say that didn’t make the Nation of Islam happy.

If you listened to BOATS This Week a couple weeks ago, you’ll remember that it was February 21st, 1965 that Malcolm X was assassinated by three members of the Nation of Islam. This week’s event was a moment that set up the sequence of events that would lead up to the assassination about a year later.

If you want to see the event that happened this week in history, watch the 1992 Malcolm X movie and the press conference starts about two hours and 32 minutes into the film.

If you want to hear about the assassination, as I just mentioned we covered that a couple weeks ago on episode #231 with the BOATS This Week covering February 21st, or you get a lot more historical context by listening to episode #128 of Based on a True Story where we covered the entire Malcolm X movie.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)